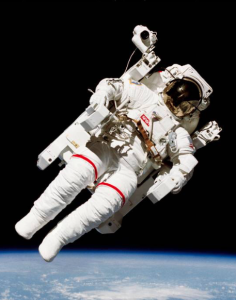

I heard an uplifting story the other day on the radio. It was an interview with the current head of NASA, Charles Bolden, who shared his experience as a youth trying to gain entrance to the Naval Academy. Mr. Bolden dreamed of becoming an astronaut, which for a black man growing up in South Carolina in the 1960s was a lofty goal indeed.

Luckily, as part of the Great Society programs, President Lyndon Johnson had dispatched a retired federal judge around the nation, looking for “nontraditional” entrants to the military academies. Mr. Bolden was saved by a nomination from a congressman from Illinois, after the entire South Carolina delegation declined to consider his application.

But then a strange thing happened. For the next several decades, at every milestone in Bolden’s career — as he progressed through his schooling, pilot training, military service and eventual acceptance into the astronaut program — a letter of congratulations would arrive. The personal note was always hand-signed by Senator Strom Thurmond, the same man who had previously turned down his request for recommendation to the Naval Academy.

The interviewer pressed Bolden for an explanation. Why would Strom Thurmond — a historical supporter of segregation — take such an interest in a black man whose career he had personally tried to derail?

Bolden struggled for an answer. He never inquired as to why the Senator wrote him, nor did they ever have direct contact beyond those occasional, one-sided exchanges. But he thinks the reason lay in some change of the Senator’s moral compass, something that, sadly, he could not admit publicly.

Like the Grinch who had a change of heart, Senator Thurmond might have realized he was wrong. It’s a theory that has been debated for years — and one both Bolden and others have put forward.

In medicine, we’ve taken a long time to embrace the idea that the doctor is not always right. There was a time when questioning a senior physician or specialist consultant was considered insubordination, and risked retribution.

But once a more forgiving philosophy of care takes root, everyone on the healthcare team (including the patient) is empowered to identify — and rectify — potential errors. After all, most complex systems like health care delivery produce complex failures, where multiple people had the opportunity to correct the course but failed.

Our motto: Trust your doctors, but don’t be afraid to question them.

Knowing your fallibility, and being able to appreciate and admit when you have made a mistake, is an attribute that is harder and harder to find in America. Certainly a great deal of this behavior flows from the top leadership of our country. When was the last time you heard an elected official admit an error? When was the last time you heard it from a leader of industry?

I think the administrative folks in Flint, Michigan, have gotten close to an apology, but what got them there in the first place is more alarming than their lack of remorse. Those same state and local officials were so convinced that others had it wrong that they completely dismissed — in fact, aggressively tried to discredit — the clinician and scientists who were sounding alarm bells.

It’s hard to always be right. The amount of energy that is required to constantly defend your position in the face of competing facts or interpretations is enormous. That energy and effort could be much better directed toward understanding the position of your opponent — and in the process, enlightening your own arguments.

Out of an understanding of our own fallibility comes the ability to compromise, and we’ve clearly lost that skill, too.

I’m sorry. I was wrong. Let’s see if we can find some middle ground. We’ll be better parents, spouses, friends and citizens if we have the courage to share these thoughts with those around us. If you left these words off your Valentine’s Day card, it’s never too late to add an epilogue. And you don’t even have to buy another box of chocolates.